Dear Readers!

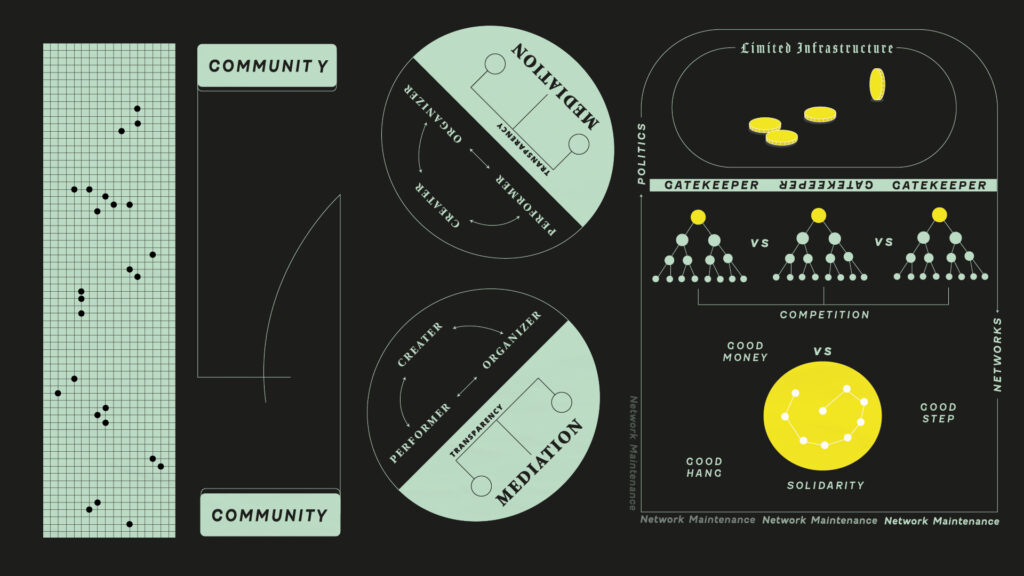

Welcome to our fourth and last newsletter, entitled Capacity Building and Artistic Self Organizing! In this text, we will dig deeper into the power relationship between institutions and individual artists and highlight how the elitist heritage of classical music affects the production structures in our field.

If you still haven’t signed up for the next Islands on the Move symposium, which will bring together practitioners from Quebec and the Nordic countries together, you can do so here! The event will be taking place on 15 December at 9.00-12.00 Quebec time / 15.00-18.00 European time on Zoom.

We would like to take the opportunity to thank you all for engaging in these matters and for contributing to the conversations in such a generous way. As said at the symposium in September, we hope that this is only the beginning and that this cluster of people will continue to grow and exchange ideas with each other going forward.

Lastly an ENORMOUS thank you to Lea for her wonderful drawings!

We hope that you’ll enjoy the reading! Brandon and Anna

Design and artworks by LEA Ye Gyoung @lealogicartist

“One of the key things to think about is the notion of capacity building, and how we construct our organizations so that time and resources can be given to things that benefit the scene as a whole.”(Peter Meanwell)

Where is the Locus of Power?

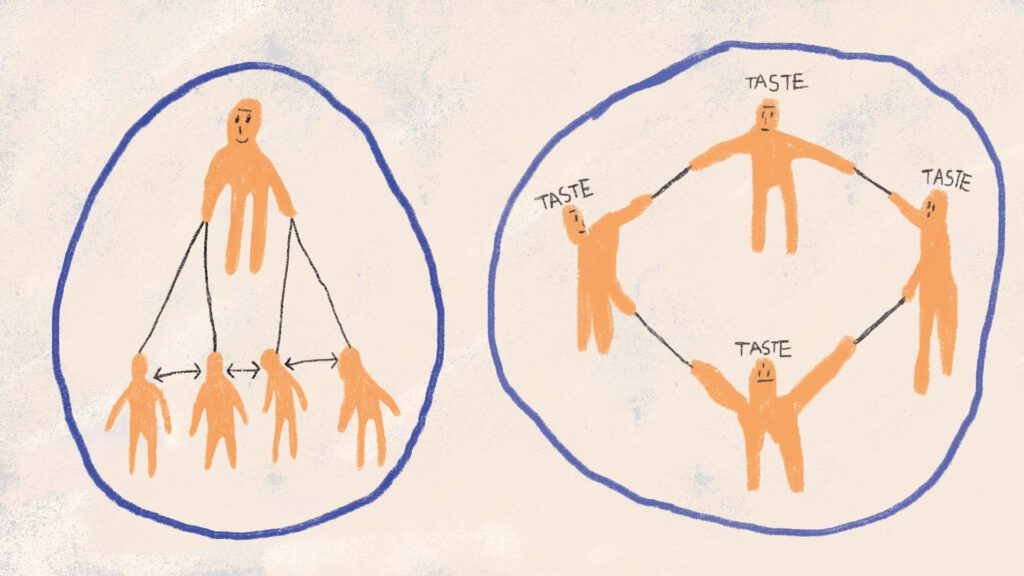

The struggle around the role of institutional leaders and how much space they should take up in the system is one of the main animating conflicts of this debate. What role should curators play? How much space should they leave to others, and what does this look like? In Taking the Temperature, Tanja Orning contrasts the different ways Lars Petter Hagen and Thorbjørn Tønder Hansen have approached to curating the Ultima Festival:

Tanja Orning: “Lars Petter Hagen’s curatorial approach […was] decisive about what he wanted and not least about what he did not want. […] This direction was not easy for the performers, because it was very difficult to get their own projects into the festival, as he wanted strong artistic control over what he curated. […]

Thorbjørn Tønder Hansen is a different type, not a composer […] but a concert organizer with extensive experience in both Oslo and Copenhagen. His curating […] is trying to bring both societal and political relevance into the festival, and addressing the Eurocentrism of how we curate. […]”

The ‘decisiveness’ of Petter Hagen’s vision for the festival turns the curator into a kind of author. From artists’ point of view, in this approach, their work becomes at worst just paint for the curator’s paintbrush, relegated to secondary importance.

But this way of working can clash especially with younger artists, who prefer to work in teams and collectives, and to experiment with alternatives to hierarchical production structures. They often organize collectively, and share the responsibilities for more practical tasks as well as for artistic decision making. How something is produced and based on what values becomes as important as what is the final outcome. Pauline Hogstrand, member of Copenhagen’s all-female Damkapellet collective, gives an insight into the challenges of integrating this ethical dimension into musical practice:

Pauline Hogstrand: “It is difficult to know if you make a choice because it makes you feel more creative, or if it is something you do by habit […] We have been struggling with the heritage of learning from the master. Often when someone does something everyone agrees, because it is easiest and it is so important for us to feel that we belong […] We have chosen not to have a formal leader, which means that everybody has to take responsibility for making decisions but without dominating the group. This of course demands a lot from the initiative-taker but also from those participating who actively need to take a more critical role.” (2021, 118)

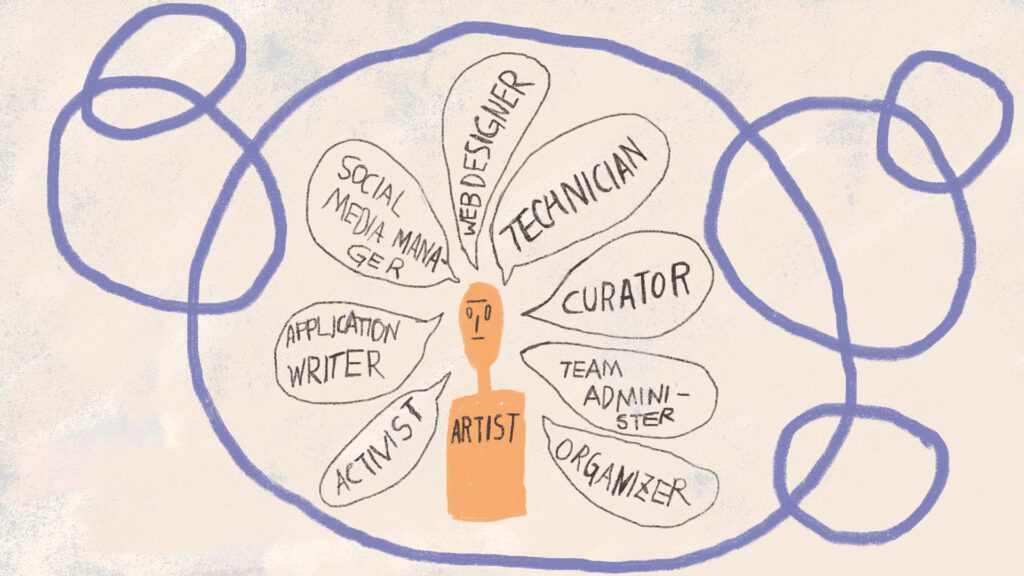

To presume a career of a long period of time, however, most freelance practitioners are obliged to work in various contexts and constantly negotiate power relationships with established institutions and festivals. This can lead to a proliferation of hierarchies and dependencies, rather than their abolishment. Danish composer Line Tjørnhøj pointed this dynamic of independent art out at the Islands on the move symposium:

Line Tjørnhøj: “For the last 10 years, I’ve mainly been living from receiving funds for projects or artworks. At one point, an artist like me comes to be exhausted. There are no support systems. I don’t have an organization, every time my project ends, all the qualified people in my little network disappear because they need to take on other work.”

Line’s comment is important, as the lack of support structures and solidarity networks not only drain us of creative energy, but often prevent more marginal voices from ever being heard. At the same time, it is hard to pin down what exactly these support systems should look like and what artists need (rather than stability and decent pay). Is there a middle ground when it comes to production structures that allows for artists to be artists (and not primarily entrepreneurs and organisers), but without giving up their autonomy?

In the final panel of the Islands on the Move symposium, Peter Meanwell drew from his experience as co-director for Borealis – A festival for Contemporary Music, and emphasized the competencies other than art-making which a festival can provide that are vital for our field as whole:

Peter Meanwell: “Just telling artists to ‘now you make your own festival’ without [the support of] organizations isn’t the solution. The artist isn’t necessarily the person who should be thinking about audience development for example. […] This idea that we just throw out the institution and just have artist-led [initiatives] is a really dangerous place to go. You ignore all the competencies that are needed to sustain a rich and diverse cultural field, and inadvertently replicate the structures that come from being exhausted and not having any time.”

Artists making their own festival now starts to smell of the ruggedly independent neoliberal individuals that networks like Damkapellet reject. So how can we both use stable institutions to build capacity and amplify voices, while still supporting artists and their interests in building more sustainable working networks?

Returning to Tanja Orning’s initial quote about the differences between Lars Petter Hagen and Thorbjørn Tønder Hansen’s approaches, maybe bringing the political into the festival could mean finding ways to nurture and support such networks of care could be a way of rethinking this difficult connection between how and what is performed. Perhaps if we could learn not to value certain work as more valuable than others we could find a way which would allow for a more non-hierarchical working environment which would be more sustainable for everyone involved. This however, requires in-depth-change at all levels in the field, also when it comes to the education of the next generation’s professionals in new music.

“I believe younger composers in Denmark are mostly too busy with the challenges of their individual careers to engage more in collective movements. Capitalism has transformed music into the art of solitary individuality. I am from Brazil where there is a much stronger urge for some kind of community. The conditions for artists are so bad that you have to help and support each other somehow in order to survive. It is different here in Denmark. There is not really a vibrant tradition of gathering outside the institutions for more creative purposes.” Marcela Lucatelli, composer and founder of platform SKLASH+, quote from Taking the Temperature (2021, 124)

“What happens when a movement or a small organization becomes more institutionalized? There is this gap between being a group of people doing things together, and then suddenly having the expectations from the outside to function as an institution. There is no middle ground, it is either you have to have all of this energy and be really driven, or you have to make a decision to turn it into a 9/5 job.” (Anna Jakobsson)